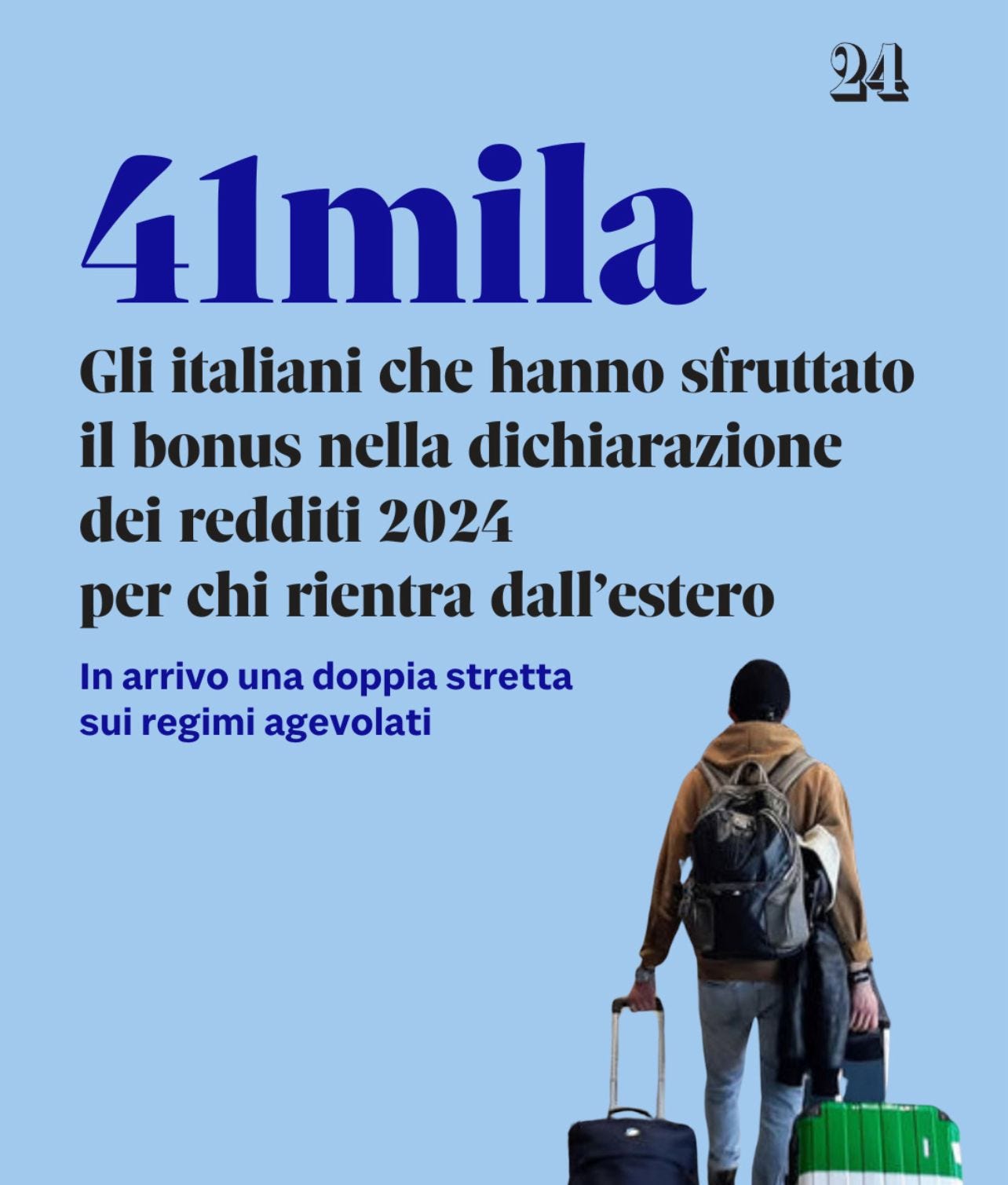

Il ritorno amaro. Perché la stretta sui bonus per chi rientra in Italia era già scritta.

A Bitter Homecoming: Why the Clampdown on Tax Incentives for Returning Italians Was Always in the Cards

La nuova norma che vieta il cumulo dei benefici fiscali per chi torna dall’estero non è una sorpresa, ma l’ennesimo segnale di una cultura politica che guarda con sospetto, e spesso con invidia, chi ha scelto di lasciare il Paese. Una punizione più simbolica che efficace, che però rischia di scoraggiare chi davvero voleva tornare.

Era solo questione di tempo. La stretta sui benefici fiscali (approfondimento su Il Sole 24 Ore) per chi rientra in Italia dall’estero, ora formalizzata nella bozza del decreto fiscale, è l’ultimo passo di un percorso cominciato ben prima, almeno 18 mesi fa, quando il governo Meloni ha scelto di ridurre drasticamente – e senza preavviso – i vantaggi per i cosiddetti "lavoratori impatriati".

Quel taglio, avvenuto a freddo, con effetto immediato e senza clausole di salvaguardia, è apparso a molti come una mossa punitiva. Un gesto più politico che tecnico, quasi ritorsivo verso quella parte di italiani che avevano “osato” costruirsi una carriera fuori dal Paese. In quel momento, era chiaro che il vento fosse cambiato: da un clima (pur intermittente) di incoraggiamento ai rientri, si è passati a una visione che, dall'alto verso il basso, tende a leggere l'espatrio come un tradimento. E ogni ritorno incentivato come un privilegio inaccettabile.

La nuova misura – che vieta di cumulare il bonus per i lavoratori impatriati con quello per i ricercatori o il regime dei neo-residenti – colpirà in realtà poche persone. Si tratta, nella stragrande maggioranza, di individui con redditi molto alti, spesso manager, startupper, grandi professionisti o ex expat che rientrano con progetti di investimento. Ma il punto non è l’impatto pratico: è il messaggio.

Quello che passa è il principio – tanto caro a una parte dell’attuale maggioranza, dalla Lega di Giorgetti, ma silenziosamente anche a una buona fetta del Parlamento a Sinistra – secondo cui chi è andato via non merita di essere favorito. Che rientrare deve essere una scelta "di cuore", non di convenienza. E che ogni incentivo fiscale, pur condizionato e monitorato, altro non è che un abuso da stroncare.

C’è poi un sentimento ben più profondo, che aleggia attorno a questi provvedimenti: l’invidia fiscale. Un tratto purtroppo tipico del nostro dibattito pubblico. In un Paese in cui il sistema tributario è oppressivo ma l’evasione diffusa, l’idea che qualcuno – anche controllato, anche per un tempo limitato – possa pagare meno tasse perché “ha fatto carriera fuori” suscita fastidio, più che comprensione. Poco importa se queste agevolazioni sono state determinanti in centinaia di storie di rientro. O se, in un mercato del lavoro ormai globale, attrarre competenze dovrebbe essere un obiettivo, non una colpa.

Le storie che ogni giorno raccontiamo su ITS Journal – di chi è tornato per la famiglia, per un’opportunità, per contribuire al proprio Paese con esperienza maturata all’estero – dimostrano che gli incentivi non sono la ragione del rientro. Ma sono spesso una leva decisiva. Rappresentano un segnale, un’apertura, un “benvenuto a casa” concreto. Smantellare quel messaggio significa, al contrario, ribadire che non è previsto un ritorno soft. Che tornare è una scelta dura, solitaria, e sempre più spesso ostacolata.

Chi rientra non cerca privilegi. Cerca riconoscimento, ma soprattutto opportunità da parte di sistema che non lo consideri un traditore. Invece, oggi come ieri, l’Italia continua a guardare con sospetto chi ha scelto di andarsene. E con fastidio chi osa tornare.

A Bitter Homecoming: Why the Clampdown on Tax Incentives for Returning Italians Was Always in the Cards

The new law banning the combination of tax breaks for those returning to Italy from abroad is less of a surprise than it seems. It's the continuation of a political mindset that views expatriates with suspicion — and returning with benefits, as a sin. A symbolic punishment, rooted in fiscal envy and national resentment.

It was only a matter of time. The latest fiscal decree puts a formal end to the possibility of combining tax incentives for Italians returning from abroad. No more overlaps between the "inpatriate" tax regime, the special tax break for researchers, or the €100k/€25k flat tax for high-net-worth individuals moving their tax residence back to Italy.

But in truth, this clampdown was written in the stars at least 18 months ago — ever since the Meloni government suddenly and drastically slashed the inpatriate regime, retroactively and without any transitional protections. At the time, the decision seemed abrupt, even retaliatory. And now, with this latest restriction, a clear political philosophy comes into view: leaving the country is seen as betrayal, and returning with tax benefits — an unfair privilege.

This new rule will realistically affect only a small group of people — mostly wealthy professionals, executives, researchers, or entrepreneurs. But that’s not the point. The real significance lies in its symbolic value. It sends a message: we do not want you back — at least not if you’re saving money by doing so.

This mindset is widespread across much of Italy’s political spectrum — especially within the League and its economic ministers — and is deeply rooted in a broader cultural trait: fiscal envy. In a country with one of Europe’s highest tax burdens and one of the most widespread tax evasion rates, the idea that someone might legally pay fewer taxes — because they built a career abroad — sparks resentment, not admiration.

And yet, as countless real-life stories have shown, tax incentives are rarely the main reason people return. But they are very often the trigger that makes it financially viable to come home. They are a signal that the country is willing to welcome its diaspora with something more than rhetoric.

Dismantling that message means reasserting the old belief: returning must be hard. It must hurt. And it should not come with any perks.

Those who return are not looking for handouts — they are looking for fairness, dignity, and a system that does not treat them as traitors. But in Italy, then as now, going abroad still carries a stigma. And coming back — especially with some savings — still feels like a crime worth punishing.